Venice is its own artwork, an assemblage, pare funk, part punk, always in process, as much an idea as a place.

Where is Venice? Geographically it is a few square miles of Los Angeles that borders the Pacific Coast just south of Santa Monica. But it is the idea of Venice, not its location, that attracts us.

Venice is L.A.'s version of SoHo or Greenwich Village or Montmartre. It is the workplace of odd-men-out who dream up new worlds and report on them through images on paper and canvas, in clay or bronze. The patron saint of such places is the shade of a stumpy-legged French aristocrat who had a taste for whores, the night and pastel drawing.

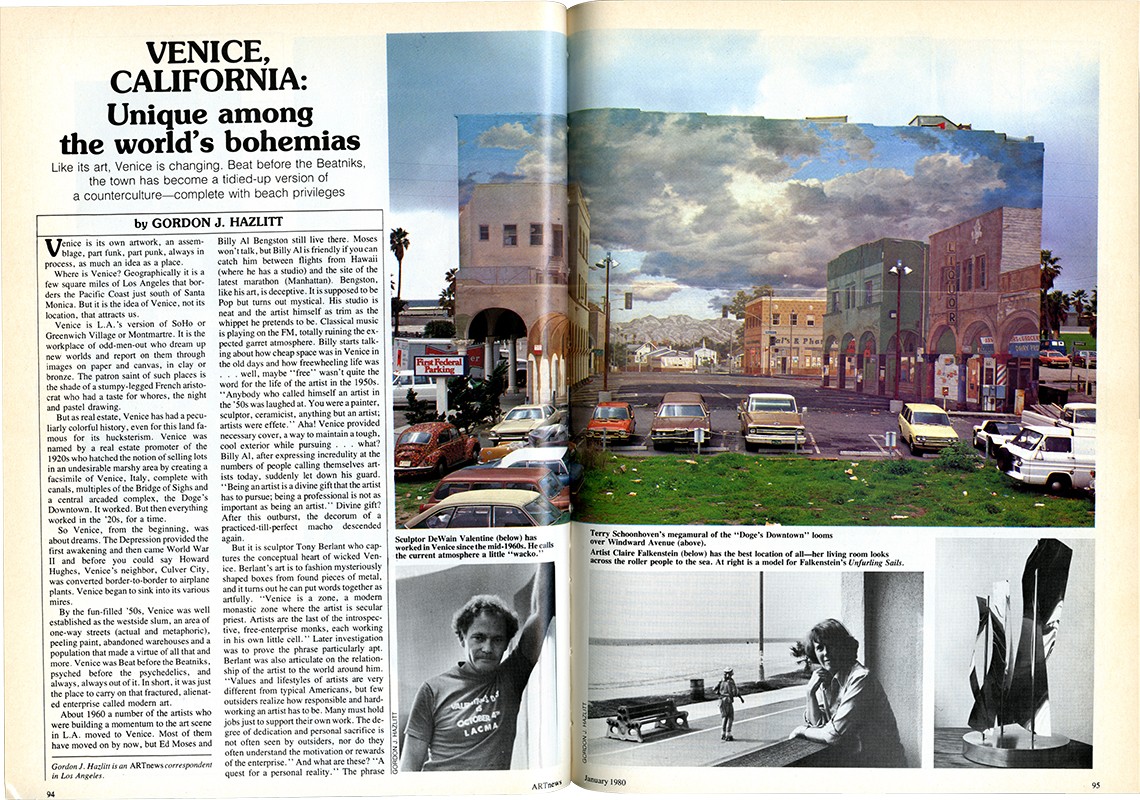

But as real estate, Venice has had a peculiarly colorful history, even for this land famous for its hucksterism. Venice was named by a real estate promoter of the 1920s who hatched the notion of selling lots in an undesirable marshy area by creating a facsimile of Venice, Italy, complete with canals, multiples of the Bridge of Sighs and a central arcaded complex, the Doge's Downtown. It worked. But then everything worked in the '20s, for a time.

So Venice, from the beginning, was about dreams. The Depression provided the first awakening and then came World War II and before you could say Howard Hughes, Venice's neighbor, Culver City, was converted border-to-border to airplane plants. Venice began to sink into its various mires.

By the fun-filled '50s. Venice was well established as the westside slum, an area of one-way streets (actual and metaphoric), peeling paint, abandoned warehouses and a population that made a virtue of all that and more. Venice was Beat before the Beatniks, psyched before the psychedelics, and always, always out of it. In short, it was just the place to carry on that fractured, alienated enterprise called modern art.

About 1960 a number of the artists who were building a momentum to the arc scene in L.A. moved to Venice. Most of them have moved on by now, but Ed Moses and Billy Al Bengston still live there. Moses won't talk, but Billy Al is friendly if you can catch him between flights from Hawaii (where he has a studio) and the site of the latest marathon (Manhattan). Bengston, like his art, is deceptive. It is supposed to be Pop but turns out mystical. His studio is neat and the artist himself as trim as the whippet he pretends to be. Classical music is playing on the FM, totally ruining the expected garret atmosphere. Billy stares talking about how cheap space was in Venice in the old days and how freewheeling life was, well, maybe "free" wasn't quite the word for the life of the artist in the 1950s. "Anybody who called himself an artist in the '50s was laughed at. You were a painter, sculptor, ceramicist, anything but an artist; artists were effete." Aha! Venice provided necessary cover, a way to maintain a rough, cool exterior while pursuing…what? Billy Al, after expressing incredulity at the numbers of people calling themselves artists today, suddenly let down his guard. ''Being an artist is a divine gift that the artist has to pursue; being a professional is not as important as being an artist. " Divine gift? After this outburst, the decorum of a practiced-till-perfect macho descended again.

But it is sculptor Tony Berlant who captures the conceptual heart of wicked Venice. Berlant's art is to fashion mysteriously shaped boxes from found pieces of metal, and it turns out he can put words together as artfully. "Venice is a zone, a modern monastic zone where the artist is secular priest. Artists are the last of the introspective, free-enterprise monks, each working in his own little cell." Later investigation was to prove the phrase particularly apt. Berlant was also articulate on the relationship of the artist to the world around him. "Values and lifestyles of artists are very different from typical Americans, but few outsiders realize how responsible and hardworking an artist has to be. Many must hold jobs just to support their own work. The degree of dedication and personal sacrifice is not often seen by outsiders, nor do they often understand the motivation or rewards of the enterprise." And what are these? ''A quest fur a personal reality." The phrase takes on character in Berlant's work. He mixes humor and found objects in fashioning his poetic, ironic sculpture pieces. Some time ago, while remodeling a room in his old house (another favorite California pastime), Berlant found a hidden cache of tiny industrial diamonds. They inspired him to create a series of very small metal collages in which the diamonds were incorporated. These pieces could be hung on the wall or pinned to a garment and worn as jewelry. Berlant playfully built this double duty into them to prolong their lives within the consciousness of their owners. Like other artists, he is concerned about the ''life after studio" of the objects he makes. Objects that are dispersed through the market, like high-status furniture, tend to "disappear'' because they become so familiar that people don't look at them any more . It is characteristic of Berlant's sculpture chat it moves about in place and function, thus resisting annihilation by habituation.

But Venice, like its art, is changing. Right now the place has a bad case of the Chic. The Pacific Ocean Park area, where the amusement pier used to be, has already metamorphosed into upper-middlc-classcraftsy-cute. It has been common in bohemia that real estate values rise with the reputations of the resident artists, but Venice is different in that it has twin nemeses: real estate and the beach. The beach is a longstanding, potent southern California tradition which by proximity has made Venice unique among the world's bohemias. Could you imagine, for instance, Toulouse-Lautrec sketching surfing girls rather than the ladies of the night?

For a long time, the beach and money didn't go together, but now all those folks with all that new money like the beach and the clean air and, since they don't really believe in their own prosperity, they like to associate themselves with a tidied-up version of a counterculture. Neo-Venice emerges. The latest hundred-odd unit condominium development, located right where the fun house used to be, sold out at a hundred thousand plus per unit before it was finished.

The money creeps closer. Painter Laddie Dill reports that the old warehouse he and Tom Wudl share as a studio was recently sold to "foreign money" for $950,000. Not surprisingly, they now have lease problems. The only artists continuing to work in Venice are those who got in early enough to buy their own buildings or those who arrived with an income to sustain them. Younger or less affluent artists now are moving to downtown L.A., where some low-cost loft space can still be rented.

One fatal temptation in discussing Venice and its artists is to assume and then look for a common clement in their style. There is none, and the proof was plain to see in four recent exhibitions of four artists from Venice recently shown throughout L.A. De Wain Valentine has worked in Venice

since the mid-1960s; he was one who bought his own space and is secure. When I visited him, De Wain and his crew were sporting red T-shirts with the message "Valentine's Day is October 4th at LACMA. "The self-advertisement referred to a show of his new glass structures he had just installed at the Los Angeles County Museum. Valentine's considerable reputation as a sculptor was based on large cast-resin prisms, and the new work is definitely a departure. Using one-inch strips of plain window glass, fashioned into extended truss structures, Valentine has fabricated a world that is as solid as geometry and yet light at the same time. The centerpiece is a double pyramid, nearly eight feet tall, constructed of triangulated trusses. In the white light it shimmers and actually casts gray and white shadows. It is pure visual magic.

Across town, at the Municipal Gallery, Ruth Weisberg offers a survey of her recent drawings, paintings and lithographs. Weisberg is not as well known a Venicite, but, he is master of an old, honored art. She not only employs the figure, often in an autobiographical context, but plays with the images in terms of the history of art. The figure of Giles, from Watteau, appears in some of her scenes. Old people and young dancers are juxtaposed in images and raise issues and feelings of mortality. Renaissance architectural facades, theater curtains and mirrors are other symbol-images she uses as she mines her own humanity. To see her work is to be reminded that contemporary art need not always be cool and distant to human concerns. It is a tricky task chat easily could devolve to sappiness, but it is a measure of her skill that the pictures reverberate in memory.

Onward to old La Cienega and the Rosamund Felson Gallery, where Chris Burden is astride a motorcycle (securely attached to a wooden sledge). The cycle is positioned so that its back wheel rubs against the surface of an eight-foot-round cast iron flywheel that is also secured by a wooden framework. As the motorcycle revs up, the giant flywheel spins faster and faster with a menacing momentum. The noise, the vibration and the stink are overpowering. In another room are displayed some sort-of assemblages and sort-of sculptures for sale. Most have rather transparent themes related to violence and death.

Meanwhile, back in Venice itself, at an annex of the Janus Gallery, young artist Eric Orr presented a series of works called "Chemical Light: Bas Reliefs in Lead and Gold." That title perfectly describes the very low-key transformation Orr has wrought with that basest of all metals, lead. He has spread thin sheets of lead over square or rectangular panels, then scored them, often in repeated diagonals, and sprayed bands of gold paint. The material per se is very evident, but what emerges is a sense of landscape, chunks of the heavy weather one often sees westward over the sea in winter. The effect is alchemic: to produce air, water and space from lead. At another level, these pieces stand as a neat symbol for what has been going on in Venice studios.

In the past five years, Venice has become a minor center for the selling as well as the making of art. Peter Gould opened his L.A. Louver Gallery (the name is a play on the French museum and a louver-type window often employed in California tract houses), and Doug Christmas moved Ace Gallery to Venice in 1975. Gould located in Venice because the low rent gave him time to establish himself, and Ace moved there to find a larger space in which to exhibit the big pieces of Caro, Warhol, Rauschenberg and others. Then Jan Turner relocated her Janus Gallery in a handsome space just a few steps from the walkway beside the beach. Though none of the three has particularly focused on Venice-based artists, Janus Gallery has consistently been the most adventurous, showing conceptual and narratively based work along with other advanced forms. L.A. Louver has built a solid reputation representing some local artists and maintaining a strong British connection. It turns out that British painters like Los Angeles, just as their ancestors liked the South of France. Recently a store called Bookworks opened in the heart of Venice and it offers a collection of books created by artists that is second to none in the nation. And in nearby Ocean Park, actress Faye Dunaway and a friend have ventured the Dunaway O'Neill Associates, Inc., a space that has been showing some handsome work of younger, not-so-well-knowns.

Back on Windward Avenue, underneath megamuralist Terry Schoonhoven's marvelous trompe l 'oeil mural, the skaters roll on. Disco roller skating is the latest fad, and young and would-be young alike may be seen day and night gliding along. Where the Beats sought freedom by screaming at the establishment, and the drug people by inject ing themselves, these roller people just float around. De Wain Valentine called the current Venice atmosphere a little "wacko." Values have been reversed. The old garret mentality that spawned modernism so long ago now withers and worries in uneasy splendor. Success, not rejection, is the concern of most Venice artists today. Yet outside it. seems as if the whole world lives unconventionally, bloating bohemia beyond all recognition. What's a poor artist to rebel against these days?

A few steps away is Laddie John Dill 's million-dollar ware house. Dill has worked in both New York and Los Angeles. He was reared in Malibu, educated here, and recalls that when he graduated, "it was impossible for young artists to do anything here . If you were any good, you left town." He came back because he found New York's street scene completely absorbed him. Venice is quiet, and inside his studio one can just hear the lapping of the waves. But Dill is much more optimistic now and feels southern California has grown in sophistication, an attitude that was reinforced by his recently completed commission for a l2-by-18-foot mural for the lobby of a new Westwood office building. He was especially pleased that it could be seen from the street; to a Californian, the view from the car is important. But Dill still looked worried. Partly it was the legal hassle over the lease, but that couldn't be too worrisome for he mentioned he had bought a commercial lot and was working with an architect to build a complex of studio-living spaces. His plan, in the grand California manner, is to build several, sell some and keep one. In the big pictures on the walls Dill combines concrete and glass in abstractions that have the sweep of geologic space in them. He explained how he controls the concrete, then hinted that he wasn't so sure he wanted to be stuck in this particular material for the rest of his career." I would say the work is going…towards painting. Yes, definitely towards painting." Pause. Wrinkle of brow. "I am learning to leave things open and not program myself so firmIy."

One cannot survey a place where artists work and not be struck by how many more women artists are at work today. The grande dame of Venice, the lady who has been there from the start, is Claire Falkenstein. She worked for 13 years in Paris "developing her concepts" before moving to Venice early in the 1960s. She says she came to Los Angeles because it is "a city that is open and still becoming." The same might be said for this expansive sculptor who looks like your favorite aunt, except for the blowtorch in her hand. Falkenstein's studio looks like a body shop, and her assistant is a body man who moonlights by helping her create her pieces. She was one of the first artists in Venice to build her own space and she has the best location of all; her living room looks right across the walkway and sand to the sea and horizon beyond. We sat on her porch, ate carrot cake and talked or her sculptural concerns for topology, the sign and truss structures. The view before us was just right for the conversation.

Gloria Kisch and Lita Albuquerque are successful artists, friends and representatives or a lacer wave of Venice creativity. They are very "aware" young women, and in a sense they typify the search for new sources that some commentators see coming from the artistic branch of the women's movement.

Gloria Kisch speaks of her sculpture as being about "psychological issues." She has slowly moved from painting (which she now disowns) to totemistic stick forms that leaned against the walls, to a series of rather awkward "Gates," which leaned out further from the walls, to freestanding sculpture, and a recent trip to New Guinea inspired her to create larger environmental pieces. Some of these are called "Chimes" and they incorporate actual stones with fabricated steel structures. Her work is based on primitive an and the best of it does possess a totemistic power. Kisch loves Venice for the space it has given her to grow as an artist and a person. She gives warm testimony to the supportive fellowship that exists among artists and recalls times when more established artists would bring critics around to see her work.

Lira Albuquerque is a successful painter who has just moved back into Venice. She and her husband. Steve Kahn, an artist and photographer, had just finished building a 7,000-square-foot combined living-studio rental

space. Garret indeed! The conversation that followed and the presence of the new, handsome structure played in ironic counterpoint. Albuquerque—it is her father's name, not an assumed place name—calls herself an imagemaker, one who brings forth images and who is concerned with the relationship between man and nature's languages. She speaks of the need to revive the role of the artist as shaman so art can again "speak to spiritual things." Recently she has been going out of the studio and working directly on the earth, creating what she calls "Terrestrial Paintings." Inside the images continue to flow onto the canvases with the fluidity of speaking in tongues. Basic geometric forms of triangles and circles emerge from dark primal grounds. and squiggly lines suggest proto languages: the work is as colorful and as nonthreatening as its creator.

As the conversation concludes, the workmen continue to haul sheets of plywood up to the second floor to complete Steve's studio-darkroom. In Kahn's work, very enlarged photographs of doors and windows are juxtaposed over views of cityscapes in ways that work shamanistic, perceptual tricks. Seven thousand square feet of plywood and stucco may seem an odd environment for a shaman to work in, but maybe this is precisely the combination we need in these waning years of the 20th century.

Caption: Terry Schoonhoven's megamural of the "Doge's Downtown" looms over Winward Avenue (above).