"One curious thing about Los Angeles is the way beautiful things are allowed to happen suddenly. Everybody is ready to accept a beautiful thing here," said Vic Henderson.

"Then, just as suddenly, a beautiful thing can be thoughtlessly destroyed."

Henderson is a young, blue-eyed, Jesus-hippie-style painter, one of the two permanent members of the L. A. Fine Arts Squad. He sighed slightly, shoulders sagging. It was a gentle reaction for a man who watched one-third of his life's work vanish from sight in less than six months.

Terry Schoonhoven, the other Squad member, slumped in a kitchen chair wearing a scuffed leather jacket, long, matted hair and wispy whiskers. He was quieter but perhaps angrier. Both artists live with a certain philosophical resignation.

The LA Fine Arts Squad paints oversize murals on neglected Los Angeles walls. Since 1969 it has executed four and is now finishing a fifth in Thousand Oaks, a shopping center out in the San Fernando Valley. The Squad also did a fool-the-eye cutout of a submarine that startled the genteel residents of Newport Beach in 1970 when it surfaced in Balboa Harbor among the white luxury yachts. Another 01 its efforts was Hippie Know-How, a minor effort executed in 1972 for the Paris Biennale with the help of young French artist Paul Martin.

Both Henderson and Schoon hoven come from small Midwestern towns, Henderson's in Ohio, Schoonhoven's in Illinois. Both feel their attachment to figurative painting comes from childhood memories of the kind of art admired by small-town people. Schoonhoven remembers dreaming over books of old-master reproductions as a child. Henderson copied Frederick Remington as well as his own father, who was a successful commercial illustrator for the old Fortune Magazine.

Both are academically trained. Both have B.A. degrees but dropped out of master's programs to paint walls. After a bout with abstraction, Henderson turned, in the late '50s, to a representational style; he admired Diebenkorn, Bischoff and Park. Schoonhoven has always been a figurative artist.

Despite the fact that the Squad seems to operate out of an ideology suggesting hippie commune life and an attack on "the personality cult" in art, Henderson denies any consciously taken political postures. ''It just seemed our individual identities didn't matter as long as people knew the paintings were done by the Fine Arts Squad," he said.

Henderson and Schoonhoven work out themes and designs together through rap sessions that uncover personal fantasies in which they share equally. Neither has a separate artistic career, although neither of them rules out the possibility in the future.Their murals are true collaborative efforts: and a passionate dedication to their murals invariably interrupts other individual projects undertaken for personal satisfaction.

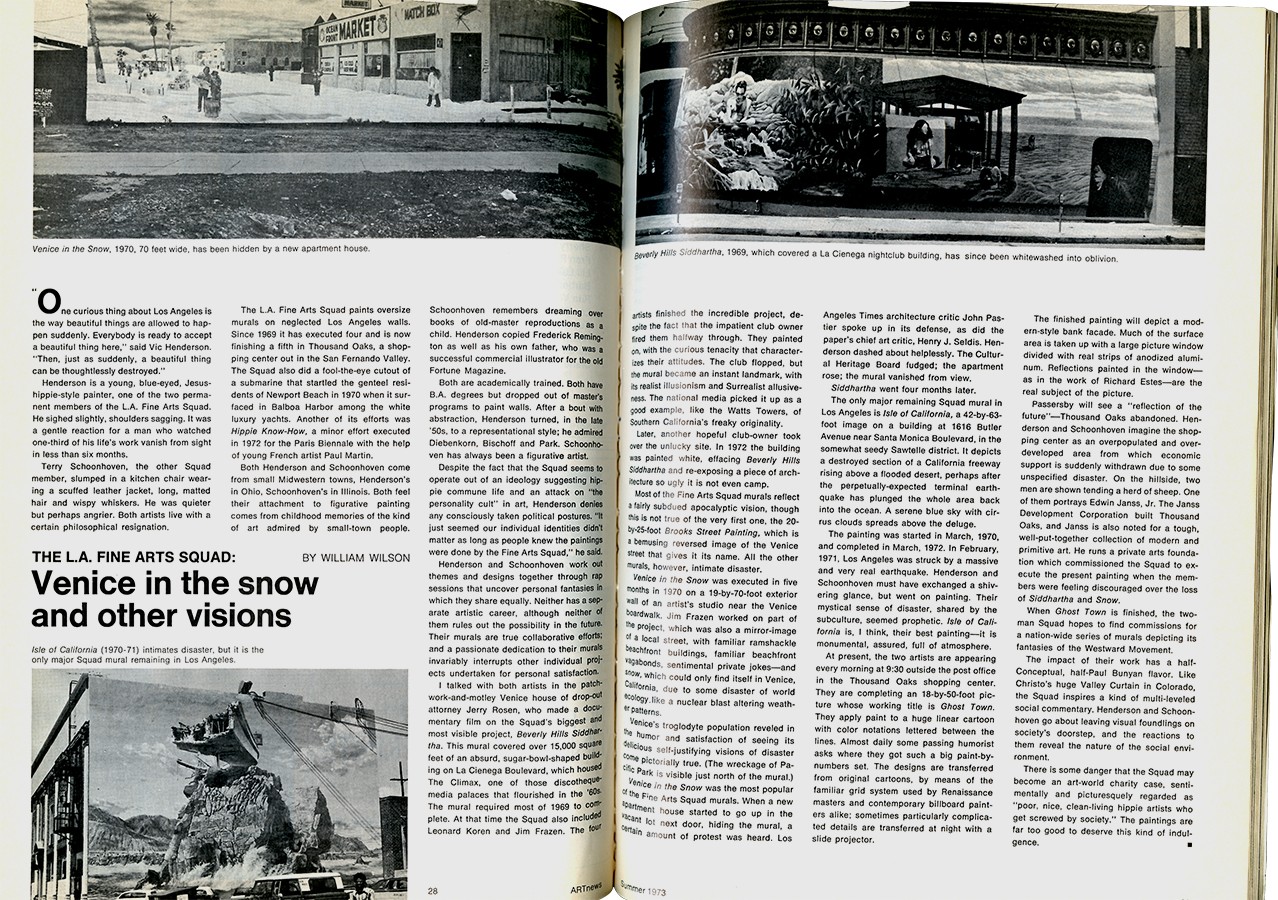

I talked with both artists in the patchwork-and-motley Venice house of drop-out attorney Jerry Rosen, who made a documentary film on the Squad's biggest and most visible project, Beverly Hills Siddhartha. This mural covered over 15,000 Squall feet of an absurd , sugar-bowl-shaped building on La Cienega Boulevard, which housed The Climax, one of those discotheque-media palaces that flourished in the '60s. The mural required most of 1969 to complete. At that time the Squad also included Leonard Koren and Jim Frazen. The four artists finished the incredible project, despite the fact that the impatient club owner fired them halfway through. They painted on, with the curious tenacity that characterizes their attitudes. The club flopped, but the mural became an instant landmark, with its realist illusionism and Surrealist allusiveness. The national media picked it up as a good example, like the Watts Towers, of Southern California's freaky originality.

Later, another hopeful club-owner took over the unlucky site. In 1972 the building was painted white, effacing Beverly Hills Siddhartha and re-exposing a piece of architecture so ugly it is not even camp.

Most of the Fine Arts Squad murals reflect a fairly subdued apocalyptic vision, though this is not true of the very first one, the 20-by-25-foot Brooks Street Painting, which is a bemusing reversed image of the Venice street that gives it its name. All the other murals, however, intimate disaster.

Venice in the Snow was executed in five months in 1970 on a 19-by-70-foot exterior wall of an artist's studio near the Venice boardwalk. Jim Frazen worked on part of the project, which was also a mirror-image of a local street, with familiar ramshackle, beachfront buildings, familiar beachfront vagabonds, sentimental private jokes�—and snow, Which could only find itself in Venice, California, due to some disaster of world ecology. Like a nuclear blast altering weather patterns.

Venice 's troglodyte population reveled in the humor and satisfaction of seeing its delicious self-justifying visions of disaster come pictorially true. (The wreckage of Pacific Park is visible just north of the mural.)

Venice in the Snow was the most popular of the Fine Arts Squad murals. When a new apartment house started to go up in the vacant lot next door, hiding the muraI, a certain amount of protest was heard. Los Angeles Times architecture critic John Pastier spoke up in its defense, as did the paper's chief art critic, Henry J. Seldis. Henderson dashed about helplessly. The Cultural Heritage Board fudged; the apartment rose; the mural vanished from view.

Siddhartha went four months later. The only major remaining Squad mural in Los Angeles is Isle of California, a 42-by-63-foot image on a building at 1616 Butler Avenue near Santa Monica Boulevard, in the somewhat seedy Sawtelle district. It depicts a destroyed section of a California freeway rising above a flooded desert, perhaps after the perpetually-expected terminal earth quake has plunged the whole area back into the ocean. A serene blue sky with cirrus clouds spreads above the deluge.

The painting was started in March, 1970, and completed in March, 1972. In February, 1971, Los Angeles was struck by a massive and very real earthquake. Henderson and Schoonhoven must have exchanged a shivering glance, but went on painting. Their mystical sense of disaster, shared by the subculture, seemed prophetic. Isle of California is, I think, their best painting—it is monumental, assured, full of atmosphere.

At present, the two artists are appearing every morning at 9:30 outside the post office in the Thousand Oaks Shopping center. They are completing an 18-by-50-foot picture whose working title is Ghost Town.They apply paint to a huge linear cartoon with color notations lettered between the lines. Almost daily some passing humorist asks where they got such a big paint-by-numbers set. The designs are transferred from original cartoons, by means of the familiar grid system used by Renaissance masters and contemporary billboard painters alike; sometimes particularly complicated details are transferred at night with a slide projector.

The finished painting will depict a modern-style bank facade. Much of the surface area is taken up with a large picture window divided with real strips of anodized aluminum. Reflections painted in the window —as in the work of Richard Estes—are the real subject of the picture.

Passersby will see a "reflection of the future"—Thousand Oaks abandoned. Henderson and Schoonhoven imagine the shopping center as an overpopulated and overdeveloped area from which economic support is suddenly withdrawn due to some unspecified disaster. On the hillside, two men are shown tending a herd of sheep. One of them portrays Edwin Janss, Jr. The Janss Development Corporation built Thousand Oaks, and Janss is also noted for a tough, well-put-together collection of modern and primitive art. He runs a private arts foundation which commissioned the Squad to execute the present painting when the members were feel ing discouraged over the loss

of Siddhartha and Snow.

When Ghost Town is finiShed, the two-man Squad hopes to find commissions for a nation-wide series of murals depicting its fantasies of the Westward Movement.

The impact of their work has a half-Conceptual, half-Paul Bunyan flavor. Like Christo's huge Valley Curtain in Colorado, the Squad inspires a kind of multi-leveled social commentary. Henderson and Schoonhoven go about leaving visual foundlings on society's doorstep, and the reactions to them reveal the nature of the social environment.

There is some danger that the Squad may become an art-world charity case, sentimentally and picturesquely regarded as "poor, nice, clean-living hippie artists who get screwed by society." The paintings are far too good to deserve this kind of indulgence.